Bihar child rapes: Regular social audits must in shelters, says professor whose report exposed case

8 min read The brutal sexual and physical abuse of at least 34 out of 44 minor girls at a shelter home in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur town came to light because of a social audit of 110 shelter homes commissioned by the state government. The audit was conducted last year by a team from Mumbai’s Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and its report, submitted to the government in April, revealed that various forms of abuse were prevalent in almost all institutions.

The brutal sexual and physical abuse of at least 34 out of 44 minor girls at a shelter home in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur town came to light because of a social audit of 110 shelter homes commissioned by the state government. The audit was conducted last year by a team from Mumbai’s Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and its report, submitted to the government in April, revealed that various forms of abuse were prevalent in almost all institutions.

In Muzaffarpur’s Balika Grih, a short-stay shelter home for lost or destitute girls, medical examinations and police inquiries have revealed that the girls, aged between seven and 18, had been repeatedly raped, tortured, cut, beaten and locked up by various staff members. One of the inmates has also claimed that the body of a girl was buried on the premises of the shelter home, which is funded by the state and run by a non-profit organisation called Seva Sankalp Evam Vikas Samiti.

The Bihar police has arrested 10 of the 11 accused so far, including the key accused and the head of the non-governmental organisation, Brajesh Thakur. On Sunday, the Central Bureau of Investigation took over the case.

The investigation is now expected to take its course, and details about the horrific abuse in Muzaffarpur are likely to keep making headlines. But Mohammed Tarique, the assistant professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences who led the social audit, points out the need to ask larger questions about the systems that enable such violence and abuse to go unreported in institutions meant to protect the vulnerable.

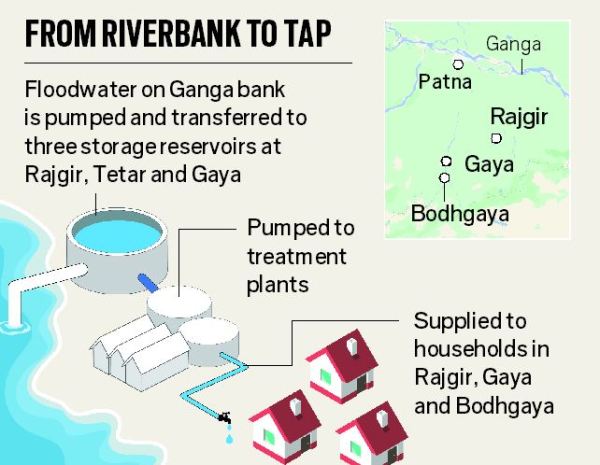

Tarique is the director of the Koshish Field Action Project at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, which has been working on issues of urban poverty since 2006. Speaking to Scroll.in from Patna, Tarique emphasised that social audits that are mandatory and regular are the only way towards making shelter homes more accountable.

Edited excerpts:

Why did the Bihar government commission the social audit of the state’s shelter homes last year? Was this the first time such an audit was done?

We audited 110 institutions over six months, and they included old age homes, short-stay homes for women and children, shelters for homeless beggars, adoption centres, and more. The principal secretary [of the state’s social welfare department] had concerns about how these institutions were being run. In Bihar, the government runs very few shelter homes directly – most of them are run by NGOs funded by the government. The objectives of the audit were to understand if there are specific requirements that these NGOs have to increase their efficiency, and to know if they are facing any difficulties vis-à-vis working with the government. The aim was to arrive at corrective measures for the problems that they have. But probably nobody thought that these kinds of things would come out of the audit.

As far as I know, this is the first social audit of shelter homes that has been commissioned in Bihar, and no other state is doing this. Even today, we do not have social audits as a mandatory part of our social welfare programmes.

What was the methodology of your social audit?

We were a team of eight people, and every home was visited by three to four of us. We spoke to the heads and the staff of all of the institutions and understood from them what things they needed to do their work better. And we spoke to the beneficiaries of the homes – the children and women and the elderly. We held focus group discussions and also had one-to-one conversations with some of them.

We looked at the rehabilitation rate – how good or bad the institutions are at ensuring rehabilitation for people – and made an overall assessment of the quality of life of the users of these institutions. For us, it was not about checking how many mandatory government processes are being followed. Because you may not have the best of facilities and resources, but if people are being looked after well, that is what matters. In some cases where we saw grave concerns, we reported it to the government and asked them to investigate, because we are not an investigation team. What has come out in Muzaffarpur is a result of that.

What challenges or obstacles did you face in the process of auditing the shelter homes, particularly in places where the authorities themselves were involved in violence and abuse? Were you given access to the children easily?

We would not even have been able to enter these homes if the social audit was not commissioned by the government. Everywhere, we would explain the process to the institution and tell them that when we are talking to the women or children, no one should enter the room. But in many places people would still come in, with the excuse of offering tea or something or the other. We may be trying to prepare a child to share, but the moment they would see these people, they would get scared. We understood these things, so we had to make it very clear to the institutes that if anyone tried to enter, it would be treated as a serious matter.

Everybody in our team was trained to speak to children, and children are also smart enough to pick up signs. One would think that girls will only open up to the women on our team and boys to men, but that is not necessarily the case. It is about how you connect with them. We would ask, “Are you ok? Do you want to say something?” and then give them the space to talk. We clearly let them know that we were there to find out what is going on, and they do not need to be scared. And if a child said that a particular staff member was being abusive, we would not immediately pull up the staff member and risk the child getting beaten after we left.

We were able to bring all this out mainly because the context of our audit was not to unearth crime. We were also asking the institutions and staff members about their problems, and we included all of that in our report too. Our point was that a lot of institutions may be meaning to run properly, but may not have the resources. For example, there are places that need staff training to deal with people with mental or physical disabilities, or need release of funds on time. It is very easy to say that institutions are being run horribly, but we need to be fair to them because they are doing a very difficult job.

Because of what has emerged from Muzaffarpur, these other problems have been put aside, and rightly so. But these other issues do need to be addressed too. For example, there are elderly people in old age homes who can be reunited with their families but are not being reunited. They too are facing trauma.

Assistant professor Mohammed Tarique.

Since reporting child sexual abuse is mandatory under the law, did you have to take any immediate action when you came to know of sexual abuse in the shelter homes?

We could not. We had to audit 110 institutions in all. Suppose we were to ask the district administration to immediately look into abuse in one home, and we still had 70 homes to cover after that, do you think we would get to know of any such thing in the other institutes? Word would spread and we would not get access.

And we are forgetting that these are short-stay homes, so the number of children who would have entered the institutions and gone out over the years is much larger. We do not have any mechanism through which these stories come out. It could be happening across states, not just Bihar.

In the case of the Muzaffarpur shelter, it is only the gory details that are coming in the media and making news. Some journalists want to know the details of what exactly the girls said to us. This is the problem with our system – they want to make people relive their trauma. But in this entire episode, there are much larger questions that are still not being asked. And this silence is more dangerous than what has happened in Muzaffarpur.

What are the systemic problems with the state entrusting the care of children to private non-governmental organisations?

The state is accountable for welfare, of course, but all institutions – the judiciary, civil society organisations – everybody has a role. It is not that the state has no mechanisms to ensure the care of children. The Child Welfare Committee is there. But in the Muzaffarpur case, the Child Welfare Chairperson is himself an accused who is absconding. This is a larger danger, because the CWC [Child Welfare Committee] is judiciary, and if the judiciary is being accused of such a serious crime, with what confidence will people be able to report similar abuse elsewhere? Similarly, the state has also appointed child protection officers for protecting children, but in this case this officer is also an accused who has been arrested.

I will probably be hated for saying this, but this is one time where people need to come together with the state. The state here has shown that it means to clean up the system. This is very difficult to do. We are working with the social welfare department to develop systems, which are now required to address the problems that emerged in the audit. In the past two months, the department has been following up and putting in place corrective measures.

What are the corrective measures needed? Do we need to overhaul the whole system?

I am not saying that NGOs should not be allowed to run shelter homes. I am saying that we need to make them open institutions. Let people come and see how they are run, if they have nothing to hide. Let people come and speak to children and old people and others in the shelters and see how they are doing.

We need to have regular, mandatory social audits built into the system. Right now, institutions are being assessed based on how well their finances are running, how big they are, whether they are maintaining their records and submitting reports on time. But it is possible for institutes to maintain these records and registers without doing anything. For example, shelter homes are supposed to have Bal Samitis, or children’s committees, with the aim of self-determination of their needs. The minutes of their meetings are supposed to be recorded. Everywhere we went, we saw that these committees had been made and registers had been maintained, but when we asked the children, they had no idea about these committees.

That is why the only possibility for improving these institutions is having audits done by their users themselves. The criteria for evaluating organisations, whether they are good or bad, should be the experiences of the people living there. Also, the focus of the system needs to be the rate of rehabilitation of those who live there.

Courtesy: Scroll.in