Will Nitish Kumar quit his alliance with the BJP?

6 min read The Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party is on the verge of losing another partner from a long alliance. After Mehbooba Mufti’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP) in Jammu and Kashmir state, Chandrababu Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in Andhra Pradesh and Uddhav Thackeray’s Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, the next may be Bihar Chief Minister and Janata Dal (United) leader Nitish Kumar.

The Narendra Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party is on the verge of losing another partner from a long alliance. After Mehbooba Mufti’s People’s Democratic Party (PDP) in Jammu and Kashmir state, Chandrababu Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in Andhra Pradesh and Uddhav Thackeray’s Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, the next may be Bihar Chief Minister and Janata Dal (United) leader Nitish Kumar.

The ruling party is offering only two parliamentary seats to the JD(U) from Bihar’s total 40 for the 2019 general election – that’s the number of seats the Kumar-led party won in the state in the 2014 general election. The JD(U) is, however, unwilling to settle for less than 20 seats – the number it won in the 2009 Lok Sabha election.

Amid this tug of war, the possibility of simultaneous general and state assembly elections has triggered a fresh debate. “The deal being negotiated is that the BJP will get a majority share of Lok Sabha [parliamentary] seats, while Kumar will be named the candidate for state chief minister and the National Democratic Alliance’s [the BJP-led coalition in the state] undisputed leader for Bihar,” senior JD(U) sources said. But there is more than meets the eye to this.

Kumar’s metamorphosis

In the first part of his dalliance with the BJP – from 1997 to 2014 – Kumar emerged as the undisputed leader of the JD(U)-BJP coalition. Backed by ideological firepower and the political means to pull Bihar into the modern world, after nearly two decades of “misrule and lawlessness,” Kumar carved a niche for himself as an “able administrator.”

Then, for the 2015 state assembly election, Nitish became part of a ‘Grand Alliance’ with Congress and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) – the party led by Lalu Prasad Yadav, who had to step down as the chief minister of Bihar for his role in a 945-crore scam. But in 2017, Kumar made an abrupt decision to dump the Grand Alliance and regained his post as the chief minister of Bihar overnight, with the saffron party’s support.

Kumar’s decision to realign with the saffron party was largely seen as a violation of the 2015 state assembly election mandate, which gave the Grand Alliance a majority.

Bihar’s law and order situation, meanwhile, has taken a beating in the past year. The exposure in April of the repeated sexual abuse of 29 girls at a state-run shelter in Muzaffarpur city helped bolster Kumar’s image as ‘Mr Good Governance.’ But he also does not seem to have much control over radical elements within the BJP, accused of pursuing a communal agenda.

Minus the charisma of Lalu Prasad and without the mass base support of caste groups, Kumar has held sway as a union minister and as Bihar chief minister in the last two decades. Now, though, he has come to be regarded as one whose brilliant past is behind him.

At the peak of his popularity in 2010 – when he was sometimes referred to as a possible candidate for prime minister – Kumar snubbed Narendra Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat at the time, during Modi’s visit to Patna.

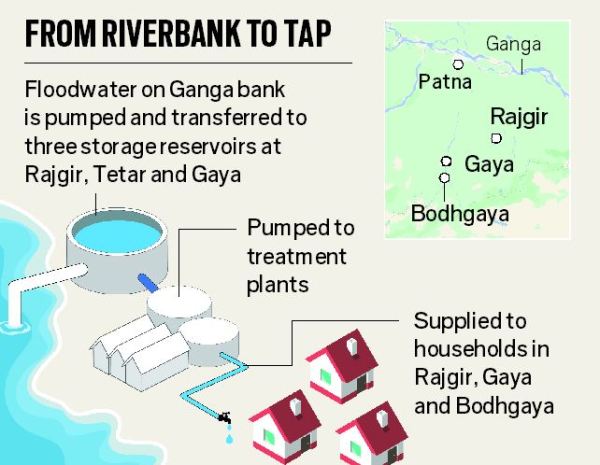

Kumar canceled a planned dinner meeting and returned a cheque Modi had sent as a relief contribution for a flooded Bihar. He even had posters of the two leaders, with their arms raised in unison, pulled down from the state capital Patna. Eight years later, when BJP chief Amit Shah arrived in Patna on July 12, the atmosphere was different. Cut-outs, posters, banners and buntings, displaying Shah and Modi, sprung up throughout the state. The route from the airport was also decorated with flower-bedecked gateways.

When he arrived at the state guest house, Shah summoned the chief minister for a breakfast meeting. Later in the evening, he reached Kumar’s house for dinner. “Kumar’s status was relegated to that of a host. The takeaway from Shah’s visit was: Modi and Shah – and not Kumar – will lead the charge for 2019. The BJP might even dump Kumar altogether after the 2020 assembly election,” said veteran Bihar watcher Mani Kant Thakur.

Bihar’s dynamic politics

Lalu Prasad’s son and the RJD’s heir apparent Tejaswi Yadav is trying to broad-base the ‘Grand Alliance.’ Bolstered by significant wins in this year’s by-elections to the Jehanabad and Araria parliamentary constituencies and the Jokihat assembly constituency, Tejaswi has reached out to allies of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance, including Ram Vilas Paswan’s Lok Janshakti Party and Upendra Kushwaha’s Rashtriya Lok Samta Party.

Kushwaha wants Kumar to withdraw his candidature for the post of chief minister for the 2020 assembly elections. “He is my leader, but must allow others a chance to become the Chief Minister,” he said. The statement is indicative of the jockeying that has begun within the NDA over seat distribution for next year’s parliamentary elections. “If alliance partners like Paswan or Kushwaha get a raw deal on account of Kumar’s hard sell with the BJP, it is rather possible that these leaders would switch camps to join the Grand Alliance at the last hour,” a veteran Bihar watcher said.

Tejaswi has also sent out feelers to the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) – led by four-time Uttar Pradesh chief minister Mayawati. Uttar Pradesh, the state with the highest number of parliamentary constituencies, plays a critical role in deciding general election results.

But when Kumar’s former political agent Prashant Kishor floated the possibility of him rejoining the Grand Alliance, Lalu Prasad’s sons Tejaswi and Tej Pratap dismissed the idea. The eldest, Tej Pratap, even put up a board saying “No entry for Nitish” outside the residence of his mother Rabri Devi, who also served as a chief minister of Bihar.

But Kumar – often regarded as a wily old fox – has mastered the art of maximizing his political position. His recent distance from the BJP seems less about re-joining the Grand Alliance and more about negotiating an honorable seat-adjustment to secure a future as the state’s predominant leader.

Recently, Kumar resurrected the demand for Special Category Status for Bihar, which will qualify the state for federal assistance in development. He also announced plans to fight against the BJP in four upcoming state elections. Second and third-rung JD(U) members also believe the party can contest all of Bihar’s 40 parliamentary seats alone. So Kumar’s message to the BJP seems to be: If it blocks his path, he will ensure it does not make big gains in the state.

The BJP leadership also appears to understand that Kumar’s loss from the NDA could galvanize the opposition and hit party prospects in 2019. “Kumar and the BJP need each other at this stage. The JD(U) and the BJP are likely to stay together until 2019. Both are likely to make concessions in respect of seat sharing,” Bihar political analyst Ajay Kumar said.

Still, the last word in the evolving dynamics of politics in Bihar has hardly been said.

The RJD is imploding with Tejaswi’s troubles with siblings Tej Pratap and Misa Bharti and Grand Alliance partners flexing their muscles in anticipation of a seat sharing discussion for 2019. “Both the Congress and RJD have performed better together. Justifiably, therefore, both must contest an equal number of seats,” said senior Congress leader Kishore Kumar Jha.

There is restlessness in the JD(U) camp as well, with legislators from the minority community in Bihar’s Seemanchal region biding their time to take the “appropriate decisions.” “In the months leading to the 2019 parliamentary elections, the politics of Bihar is likely to witness several twists and turns and desertions from all political parties can be anticipated,”DM Diwakar, a professor at the Patna-based AN Sinha Institute of Social Sciences, said.

Courtesy: Asia Times