As Corruption Returns, Bihar’s Economy Has Begun Its Descent into Chaos. Again.

8 min read Patna: The present scenario in Bihar shows that its astounding economic growth numbers, widely reported between 2010 and 2012, are rapidly declining. The story emerging from Baghlatti village in Gaya district is a testament to Bihar’s decaying economy – a true by-product of widespread corruption in the state.

Patna: The present scenario in Bihar shows that its astounding economic growth numbers, widely reported between 2010 and 2012, are rapidly declining. The story emerging from Baghlatti village in Gaya district is a testament to Bihar’s decaying economy – a true by-product of widespread corruption in the state.

“All claims for land made by 652 families under Forest Rights Act, 2006 in Baghlatti and 12 other villages were rejected by the subdivision level committee (Sherghati) and district level committee (Gaya), consequently in 2010, two years after the enactment of the Act in 2008. Ever since, the committee has never looked into the concerns of these claimants,” Ramswarup Manjhi, an activist from Bhuian community in Baghlatti told The Wire.

A PIL, in this case, was filed by the villagers in Patna high court with the backing of social organisation Janmukti Sangharsh Vahini. It was only after these step was taken that the organisation received a first interim order against the Bihar government.

Where Odisha has given forest rights on five lakh acres of land to 3.5 lakh persons, Bihar has made no progress in this regard. After the enactment of FRA, 2006, out of 50,000 to one lakh potential claimants, merely 28 persons have been settled so far, that too on lesser than one acre of land.

According to a high court order dated July 27, 2017: “The grievances of the petitioners (under FRA) seems to be that cases are not being decided in accordance with the requirement of the Statute. Cryptic orders are passed contrary to the requirement of the rules… It is decided that during the pendency of the matter of an individual concerned, he shall not be dispossessed and status quo shall be maintained.”

Operation Bhoomi Dakhal Dahani

What Operation Bhoomi Dakhal Dahani – a land reform campaign started in September 2014 – achieved was that the land claims of 17.4 lakh families in Bihar were identified by the state government for the first time. However, surveys from civil society groups show that about 80% of the 1.5 lakh families claimed to be given land possession have not been settled. Aarti Verma from the Primary Agricultural Credit Society (PACS), whose organisation had also volunteered to do these surveys, confirmed this eyewash.

Pankaj, an activist from West Champaran and a member of the land reform core committee formed by state revenue department before the campaign, said, “It was claimed by the officials that the land claims of 12,000 families in Champaran were identified under Operation Bhoomi Dakhal Dahani, out of which 900 families have been given possession. I and other activists visited these families. We were horrified to find that most of the families among the 900 were of those who already possessed their claimed land and were cunningly re-identified and not provided land in this drill. Instead, they lost the land they earlier possessed on paper under Operation Bhoomi Dakhal Dahani. The possessions being upgraded on paper came out to be a farce in reality. What has been achieved is mere acknowledgement of people’s land claims.”

When Vyas Jee, who served as the principal secretary of the state revenue department till 2016, was contacted, he said, “The campaign Operation Bhoomi Dakhaldahani was systematically conducted across Bihar’s 38 districts after discussions among the members of an efficient core committee. However, it is unfortunate that the core committee, which saw representation from the department, A.N. Sinha Institute in Patna, civil society groups, advocates and academicians, has now become dysfunctional. The acting officials with the revenue department should reconstitute the committee and continue with the campaign. I don’t see the campaign as a failure, it’s still ongoing.”

Buying public posts, the new normal?

According to sources close to the Bihar government, there is no check on the increasing levels of corruption. What was achieved slowly over a nearly a decade (between 2005 and 2012) is being undone at a rapid pace by corrupt officials across all sectors.

The state of affairs was brought to light by a few vigilant citizens through social media when they posted about the corrupt practice of providing transfers as per choice to sub divisional officers (SDO). Bribes for such transfers, which have usually cost up to Rs 5 lakh, have gone through the roof and can now even be up to Rs 35 lakh.

A Munger-based official, awaiting his reposting as SDO, confirmed the practice on the condition of anonymity. He said such transactions take place openly and are well known.

“I was first posted in Sherghati sub division in South Bihar. Later, I was transferred to Betiah as SDO but to my horror, I was removed from the post within 11 months without being given a reason. I was replaced by an official who I later learnt had purchased the post by paying a hefty bribe. I was later deployed at the district transport office in Munger,” he said. “It is a sad state of affairs.”

Kanchan Bala, a social activist and former JD(U) leader, confirmed that the bribe amount to purchase high posts can even go well above Rs 35 lakh.

Today, if Bihar’s growth story is to be written amidst situations of backwardness and lawlessness, it could be dubbed Bihar’s “tryst with destiny”. Ten years after the then finance minister Manmohan Singh, on his Bihar visit, had lamented that nothing could be done about the state as it lacks infrastructure, roads, electricity and administrative infrastructure, a World Bank report published in 2006 saw possibilities of growth in Bihar and identified five areas where strategic efforts can trigger the development process.

“Improving Bihar’s investment climate, public administration and procedural reforms, strengthening the design and delivery of core social services, budget management and fiscal reform and improving public law and order,” are the areas mentioned in the report titled ‘Bihar: Towards a Development Strategy‘.

In the wake of NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant’s statement on April 24 – “The BIMARU states (refers to the poor economic conditions within the states of Bihar, MP, Rajasthan and UP) of the past continue to pull India backward on social indicators” – which suffered severe criticism from the state’s ruling party, the dynamics of Bihar deserve to be put under a microscope again.

Ebb and flow

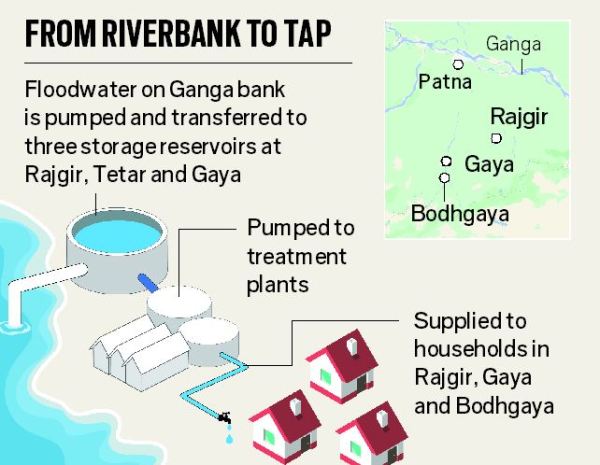

One factor here is how river water as a resource, which is available in abundance in Bihar, is simply lying unused when it could have been systematically used to generate hydroelectricity and provide drinking water, cheap transportation, navigation, irrigation and fisheries. No concrete steps have been taken to boost riverfront tourism either.

The waters of the Ganga, which enters Bihar from Uttar Pradesh, multiply 14 times by the time it flows into West Bengal. While crossing Bihar, the water from several rivers – namely Saryu, Gandak, Kamla, Balan, Kosi, Son, Punpun – merge into the Ganga. If skilled engineers built infrastructure around the rivers in Bihar for efficient utilisation of the resource, the economy could be boosted tremendously.

The waters of the Ganga, which enters Bihar from Uttar Pradesh, multiply 14 times by the time it flows into West Bengal. While crossing Bihar, the water from several rivers – namely Saryu, Gandak, Kamla, Balan, Kosi, Son, Punpun – merge into the Ganga. If skilled engineers built infrastructure around the rivers in Bihar for efficient utilisation of the resource, the economy could be boosted tremendously.

Senior engineer D.K. Mishra, who served as a water activist for years, said, “Instead of assigning an efficient team of engineers to carry out advanced engineering to enable management of river water and flood control, a poorly planned infrastructure of building dams on both sides of rivers like Kosi and Ganga was built in haste under the Bihar government’s direction. And what wasn’t even anticipated happened – because of this poor infrastructure, twice of the estimated area of land to be prevented from inundation was flooded. We bore the brunt for this faulty planning during the Kosi floods in 2008.”

“The flow of the rivers in Bihar is unstable and they will take centuries to get stable. For example, the Kosi is a river which flows in many streams One way to control the disaster could be to set up infrastructure to distribute its streams,” he said. Moreover, despite the surplus water resource, owing to the lack of technology and planning, about 50% of Bihar’s farmlands remain unirrigated.

A silver lining?

The state, where 87% of the population (against the national average of 67%) lives in villages, and where basic infrastructure is missing and there is acute power shortage, has seen some initiatives being taken over the past few years. The Nitish Kumar government successfully supervised the task of connecting small villages with a population of only around 500 people with roads and bridges. Schools building and health centres improved. Earlier, only bigger villages had such infrastructure. Moreover, 4500 MW electricity, which is three times of what was available in 2008, was made available in Bihar this summer.

The state, where 87% of the population (against the national average of 67%) lives in villages, and where basic infrastructure is missing and there is acute power shortage, has seen some initiatives being taken over the past few years. The Nitish Kumar government successfully supervised the task of connecting small villages with a population of only around 500 people with roads and bridges. Schools building and health centres improved. Earlier, only bigger villages had such infrastructure. Moreover, 4500 MW electricity, which is three times of what was available in 2008, was made available in Bihar this summer.

The land, though fertile and a vital resource, has also not led to prosperity in the state because everything that is cultivated is used to help meet the demand of the dense population.

Another important resource of the state is its workforce, but in the face of a lack of opportunities, large-scale migration has affected the state for years. The lack of industrialisation and shrinking avenues by which to earn money are the root causes that have triggered this population movement.

In fact, recently, the Bihar government notified the sale of land of several state-owned sugar mills, instead of reopening them and creating new industries.

Kingfisher’s proposal to manufacture beer from North Bihar’s ‘shahi’ litchi never materialised when Vijay Mallya fled India in 2016. Bihar’s state-owned food processing industry, which included famed brand Rasvanti, has also long been forgotten after its shutdown in the early nineties. The government still holds the burden of paying salaries to Rasvanti’s staff.

However, among the success stories are the COMFED dairy cooperative and the export of Madhubani paintings.

Reverse migrants, the future

Where increasing migration from Bihar is seen as a loss by many, the story of reverse migrants has changed the traditional ways of farmers’ exploitation statewide.

Pro-land reform political initiatives – Bhoodan, Communist movement, Ultra-Left movement, Socialist movement and Vahini movement – and the change in caste equations had put an end to the restrictions imposed by landlords over semi-bonded labourers. Post this, in the nineties, feudal control in rural Bihar loosened and artisans migrated across the country.

However, two new trends began to emerge. The downsizing of the workforce led farmers to demand better wages. Because of political and economic reasons as well, the wage rates increased. Strikingly, many landowners who were finding it difficult to pay higher wages to land tillers felt compelled to sell their lands at low rates to these reverse migrants.

The reverse migrants often return with some savings, better farming and entrepreneurship skills. This is why they have helped strengthen the economy and create avenues for Bihar’s rural workforce.

These trends, which can be seen in almost every district in Bihar, are empowering and show the way. They reflect that Bihar has inherent potential and that the human resources that are at hand could be used to write Bihar’s growth story instead of the opposite from lack of support from the government.

“Neither NITI Aayog, which views Bihar’s low Human Development Index (HDI) including the other BIMARU state’s situations as a hindrance to India’s development, nor policymakers realise that the majority of the population here is rural unlike more developed states. But a plan to improve life expectancy, education facilities and increase per capita income indicators, which trigger the HDI, was never even thought of for Bihar beyond the block level,” said Sunil Sinha, a Patna-based academician.

Whether the state is headed for prosperity or chaos now rests squarely on the shoulders of the Bihar government.

Courtesy: The Wire

Zumbish is a Delhi-based journalist from Bihar who has previously worked with The Indian Express, The New Indian Express and Ahmedabad Mirror.