Dashrath Manjhi’s village is no country for young men

6 min readThe road that Dashrath Manjhi built is now paved, marked by an arch, and flanked by a memorial being built in his honour. In election season, political parties fighting over the Mahadalit vote have been coming down it, beating a path to Gehlaur’s door. For the men of Dashrath’s village and neighbouring areas though, the road still leads only one way: out.

Many young men here have left to find work in faraway metros such as Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai. “If there is no rain in the next few days, there will be no paddy crop. The young men still around are also making plans to leave. There will be nothing to eat otherwise,” says Rajkumar Manjhi, a distant relative of Dashrath.

The massive arch that marks the beginning of the road that Dashrath built, piercing through the mountain, is the work of the Nitish Kumar government. Masons are hard at work finishing the memorial for him. However, before that could be finished, former RJD member and Jan Adhikar Party leader Pappu Yadav, currently desperate for friends, raised Dashrath’s statue in front of a shack where his family lives. The poster behind the statue, featuring both Pappu and Dashrath, dwarfs the ‘Mountain Man’.

The battle for the Mahadalit vote, the category to which Musahars such as Dashrath belong, is fierce. The lowest of the lower castes, Musahars form 5.5 per cent of Bihar’s population and have eight MLAs in the Assembly. Gaya district has the highest number of Musahars across Bihar.

Chief Minister Nitish Kumar has been wooing the vote bank for a while, including separating Mahadalits from Dalits for larger benefits. Gehlaur has been officially renamed ‘Dashrath Nagar’, and has got a health centre and school, apart from the paved road. Gehlaur admits being grateful still for Nitish’s gesture of letting Dashrath occupy the CM’s chair for five minutes in 2007.

However, the other Manjhi, Jitan Ram, former Nitish ally who is now with the NDA coalition, has upset the JD(U)’s calculations. Besides, everywhere, the CM hopeful of a “vikas (development)” vote keeps running up against charges of “not doing enough”.

Dashrath’s own family is uncertain about their loyalties. After his death eight years ago, his son Bagirath, who is slightly physically challenged, had got financial help and built a brick-and-cement hut. Bagirath’s daughter Laxmi Devi lives at her parents’ home with her three children. “We live the way we did when baba (Dashrath) was alive. Nothing much has changed,” she says. “Nitishji did a lot for baba, he respected him. Pappu Yadavji also gave Rs 1 lakh.”

For 22 years, Dashrath had stubbornly dug through a rockface with a hammer and bare hands to breach a hill to make a road in memory of his wife. In 1960, Manjhi’s wife Phalguni Devi had fallen while trudging up a narrow trail carrying his lunch and died because she couldn’t reach a hospital. The nearest town Wazirgunj was across the hill but the villagers had to take long detours until Dashrath chiselled a 25-ft wide passage for a road.

Shankar Manjhi, who claims to be Dashrath’s nephew and also lives in Gehlaur, is more charitable towards the JD(U) leader. “Nitish Kumar did a lot. You can see the road. Taar bhi de di (He gave us electricity as well).” However, he adds, “that isn’t enough to change our lives”. “This land where we live is forest land, we don’t own anything. The government promised small plots but not all have got them.”

Adding that it is not enough to just talk highly of Dashrath — “Go see how his family lives” — Shankar says, “On one side is Jitan Manjhi while Nitish is on the other. It is a difficult choice. The only thing we don’t want is Lalu’s raj again. There was no vikas (development) in his time.”

Shankar’s nephew Rajkumar, who says he had to drop out of Class X as there was no money to study further, calls “bekari (joblessless)” the area’s biggest problem. “There is no work here… And then if we get work, the daily wage is Rs 100, that too if the employer is kind.”

A little distance from Gehlaur, down the road Dashrath hammered out, Ganpati Manjhi attended a meeting held by Jitan Ram’s men recently. The paddy crop on the few bighas of land the family got under the Bhoodan scheme has failed this year, so the father of four is planning to leave for Delhi, for work in a factory earning Rs 4,500 a month. “I can send Rs 2,000-3,000 so that my children can go to school. Education is the only way out of this miserable existence.”

Agreeing that lack of jobs is a major issue, he adds, “Many among us are thinking to vote for the kamal (lotus). Nitish has done a lot but (Jitan) Manjhi is one among us.” Nearby is a memorial for seven Naxals, who were killed in an encounter in 1993. The epitaph talks about their “sacrifice for poor and underprivileged”.

Udhay Paswan’s brother Ajay Paswan is a JD(U) leader and former MLA. His large house is among the few here made of brick and cement. A car and a motorcycle are parked nearby.

“Jitan Manjhi doesn’t have any influence here,” Paswan says. “Nitishji will get most of the votes of Mahadalits. We tell people here that Nitishji placed Dashrath on the CM’s chair. At the time, who would have even dreamt of a Musahar becoming CM of Bihar? He made Jitan Manjhi CM too, but he betrayed him. Peechay se churra ghomp diya (Jitan stabbed him in the back).”

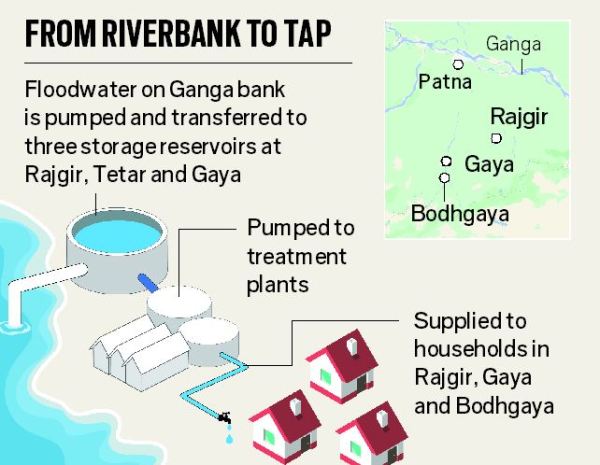

Usha Devi of Gehlaur is unruffled by the political buzz. Comparing politicans to “barsati maindak (frogs of the moonsoon)”, she says they appear “when they want our votes”. “They should first declare us human beings. Otherwise a buyian (Musahar) will always remain a buyian. Buyian sasti jati hai (Buyian is a lowly caste). We have always been treated worse than animals, and that is our life.” Pointing to a dry tap, she says she has never seen it give water. So Usha fetches “dirty” water from a well whose levels have been dropping.

In Salaya village, near the Jharkhand border, with around 30 Musahar families, a group of women is equally angry. Almost all the men of this village have migrated for work. Money comes intermittently, so the women fetch firewood from the forest nearby to sell, earning Rs 50-Rs 100 a day.

“This is how we buy food. We can’t wait for our husbands to send us money,” says Nirmala Devi, whose husband Kailo works in a hotel in Mumbai. Kabootri Devi laughs when you ask her about “government”; she has “never seen it”.

“The mukhiya (village headman) came and gave a few Indira Awas Yojana grants. There is no other help ever,” she says.

They have heard of Nitish Kumar and Lalu Yadav, but are not clear who they are. They have never heard of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Few have been to Gaya city, the district headquarters 90 km away, or even seen a train. “The contractor takes us for work in paddy fields in his truck and brings us back,” explains Chandri Devi, who lives with her three daughters-in-law and 12 grandchildren.

However, come election, she makes a trip to the polling booth — always. “We press whichever button they tell us to press,” she says, referring to the poll staff. If she could, Chandri Devi would make a better choice. “We would vote for anybody who promises work, so our men would come back to live with us.”

Courtesy: The Indian Express