Prohibition in Bihar: Widows and elderly jailed, children picked up for ferrying liquor

3 min read Over the last two years, as prohibition took root in Bihar, senior police and excise officers started mapping a worrying fallout.

Over the last two years, as prohibition took root in Bihar, senior police and excise officers started mapping a worrying fallout.

With jail figures, reported by The Indian Express Monday, showing that the state’s marginalised sections have faced the brunt of the crackdown, officials found that the real victims were the most vulnerable among them.

From 45-year-old Maya Devi of Munger, a member of the Extremely Backward Bind caste who was the first woman to be convicted under the new prohibition law, to 65-year-old Hari Das, a Dalit farm worker in Motihari district, The Indian Express tracked the faces behind the fallout to piece together a tale of helplessness and despair.

Maya Devi’s tin-roofed, one-room house in Munger’s Chhoti Muredhi village has remained shut since she was jailed last November. It was from here that police seized 25 litres of illicit country liquor in December 2016, leading to a 10-year jail term and a Rs 1-lakh fine for Maya.

Said her son Jitendra, a part-time auto driver: “After my father, who was handicapped, died a few years ago, my mother went to work in Punjab for a few months in 2015. After she returned, she started brewing mahua. When prohibition was enforced the next year, we warned her, but she said she had no other way to earn a living. Most people brewing illicit liquor here are widows, who are not trained to do anything else.”

In Motihari’s Ruhali village, Hari Das, who belongs to the Tatwa (Tanti, or weaver) Scheduled Caste, said he still did not know why he “had to spend so many days in jail” last year. Das was arrested with three others from the village by a team of the Excise department in April 2017.

“I was sitting with some fellow villagers near the fields when we were picked up. No medical test was done on any us to establish that we were consuming alcohol,” Das said.

In jail, Das said, prisoners of all kinds were bundled together. “We were put in a cell along with prisoners facing charges of murder and rape. There were other old people like me who had been jailed on alcohol charges. Fortunately, I got bail after a week, and was acquitted of all charges in July,” he said.

The other big worry, officials say, is the swelling number of youths in the illegal liquor trade. “Our estimates suggest that the number of accused between the ages of 18 and 40 is very high. The young are lured by the easy money,” Vinay Kumar, ADGP, CID, said.

A member of the child welfare committee, who spoke to The Indian Express on condition of anonymity, said “at least 20-25 per cent of children” housed in the state’s 11 remand homes were those who had been caught ferrying liquor.

“Most of these children are SCs and EBCs. Several said they took to crime because they wanted to buy smartphones. These children, mostly aged between 15 and 18 years, are paid Rs 300-500 to carry bottles in schoolbags from interstate border towns such as Sahebganj and Godda (Jharkhand), and Gorakhpur and Balia (UP) for retailers,” the official said.

“Most of these children are SCs and EBCs. Several said they took to crime because they wanted to buy smartphones. These children, mostly aged between 15 and 18 years, are paid Rs 300-500 to carry bottles in schoolbags from interstate border towns such as Sahebganj and Godda (Jharkhand), and Gorakhpur and Balia (UP) for retailers,” the official said.

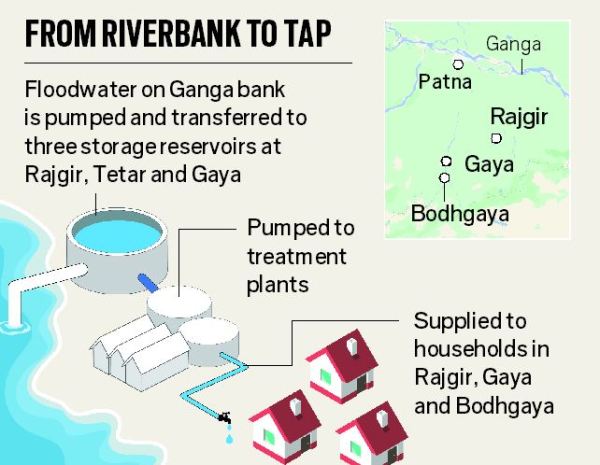

Police and excise officials say most of the liquor that enters Bihar illegally comes from across the India-Nepal border through Motihari, and from West Bengal (via Katihar), UP (via Gopalganj) and Jharkhand (via Gaya).

“We have been able to arrest only small-time traders and country liquor brewers; the big fish are seldom caught. Even when a huge consignment is seized, it is the drivers and support staff who are arrested. The ringleaders get away because they run the business smartly, by proxy,” Kumar Amit, former Excise Superintendent, Muzaffarpur, said.

Keshav Kumar Jha, Excise Superintendent, Motihari, said: “Our records show that 58 per cent of those arrested were consumers.”

According to social scientist D M Diwakar, social reform can only be initiated by raising awareness, and not through a forced implementation of rules. Prof Diwakar, who has served a director of Patna’s AN Sinha Institute of Social Sciences, said that while implementing prohibition, the government had failed to give adequate thought to related aspects such as rehabilitation.

“When a government tries to turn social reformer without alternative arrangements and rehabilitation, it is natural for youths, mostly from a poor socio-economic background, to turn to the liquor trade as an easy way of earning money. The government has failed as a social reformer. It did not look at rehabilitation, employment and governance,” he said.

Courtesy: Indian Express